Conspiracy theories are usually peripheral to most people’s lives: bemusing or irrelevant. But during a pandemic, fringe beliefs get a foothold and can become dangerous.

As Professor Julie Leask from University of Sydney’s Faculty of Medicine and Health told the ABC: “The way someone thinks and acts on an infectious disease doesn’t just affect them, it affects the health of other people.”

On Sunday, Victoria Police arrested 10 people when 100 protesters ignored coronavirus physical-distancing restrictions to stage a demonstration outside state parliament. Some were demonstrating against vaccinations. Some believed the 5G mobile network caused coronavirus.

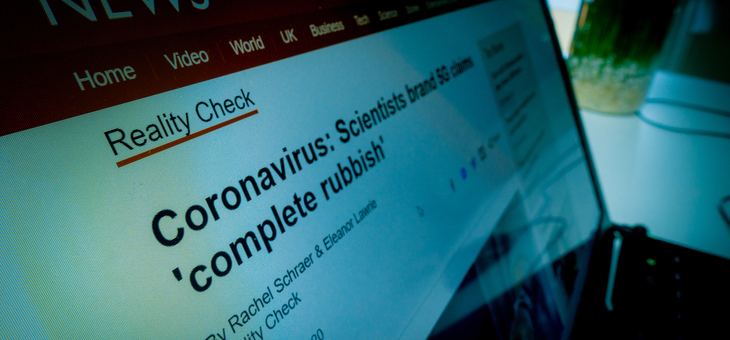

Bizarre ideas abound: COVID-19 is a giant hoax: it’s a population-control scheme; a get-rich-quick scheme hatched by big pharmaceutical companies. Some believe secret messages about coronavirus and 5G are hidden in the design of the new British £20 bill.

(All untrue.)

Prof. Leask believes people’s desire to understand and gain control of the illness creates “causal hunger”.

“People develop folk tales around disease causation, to make sense of it and find a path for prevention,” she says.

Colin Klein, an associate professor of philosophy at the Australian National University, agrees that uncertainty fuels wild speculation.

“Nobody has the full story yet.

“Government and news outlets (haven’t) been super reassuring – it may just be because there’s no reassurance to be had.”

Misinformation from ‘officials’ doesn’t help. World powers the US and China have been less than reliable sources at various stages of the outbreak. China cracked down on doctors who raised the alarm; US President Donald Trump downplayed the extent of the virus then backflipped.

Assoc. Prof. Klein says we also favour a good story to a messy, incomplete version, such as the current situation with coronavirus.

“Somebody eats a bat and they get kind of sick and nobody notices for a while and then everybody gets kind of sick is not a very satisfying story,” says Assoc. Prof. Klein. “If you were to take that to your short story writing class, people would say, ‘That’s a terrible story. Come back later’.”

The internet is part of the problem, amplifying rumours and theories. “Lies travel faster than facts and, perversely, efforts to debunk a conspiracy theory can end up reinforcing it,” says Jessica Brandt, head of policy at the Alliance for Securing Democracy in Washington, DC.

Nine journalists Sherryn Groch and Chris Zappone point out part of the reason why. “Social media algorithms favour content that generates high emotional responses in people over rational or verified sites. With no fact-checkers built into platforms, a seductive conspiracy theory has little barrier from spreading: all it needs is people to react.”

However, there’s more to it than just social media.

“Conspiracy theories are born out of the murky feeling that not all is being revealed to us, that the truth is still in shadow, and someone else is pulling the strings,” Groch and Zappone write. “During a fast-moving pandemic, where news breaks faster than scientists can make reliable findings, false credibility can attach to seemingly plausible explanations.”

Conspiracy theories have a long history in the US and arose prior to the internet. The Germans were blamed for the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918; Ebola was wrongly called a biological weapon in 2014, and the 2015 Zika crisis was blamed on “everything from vaccinations to genetically engineered mosquitoes”.

Assoc. Prof. Klein says trying to engage with “full-bore conspiracy theorists” just sucks you deeper into what they believe.

But Prof. Leask says it is possible to debunk information “quickly, calmly and respectfully”.

If dealing with a friend or family member holding such beliefs, she suggests “checking where someone first heard the conspiracy theory, about 5G causing the virus, for example, and gauging their strength of belief.”

She says: “If they seem to be simply testing out a theory, you could respond with personalised language along the lines of: ‘From what I can see, it looks like COVID-19 was caused by a virus passed from humans and that it passes from person to person.’”

She suggests “be brief, be factual, be evidence-informed, don’t shoot from the hip”.

Groch and Zappone say contesting theories with logic can work – “especially when the person pointing out the holes in the story is perceived to be smart and competent”.

“Increasingly, authorities treat such misinformation contagion like their biological equivalent – proactively pushing out the right facts to inoculate people against unfounded theories or encouraging good information hygiene (such as checking sources).”

What are the best conspiracy theories you’ve heard in relation to COVID-19? Or the best conspiracy theory ever?

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

Related articles:

Steve Perkins busts coronavirus myths

Common coronavirus questions

A doctor tackles coronavirus fake news