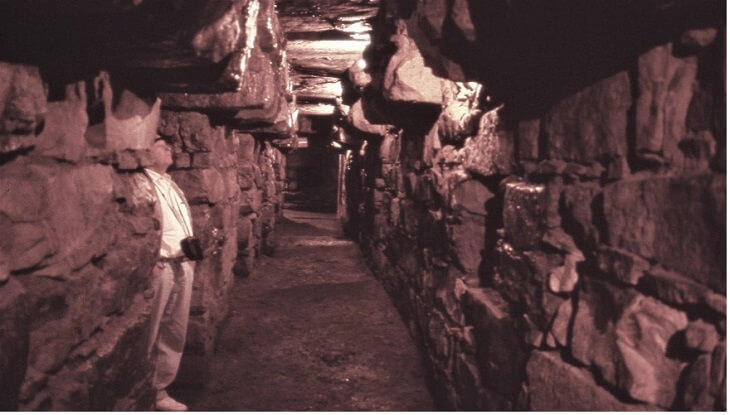

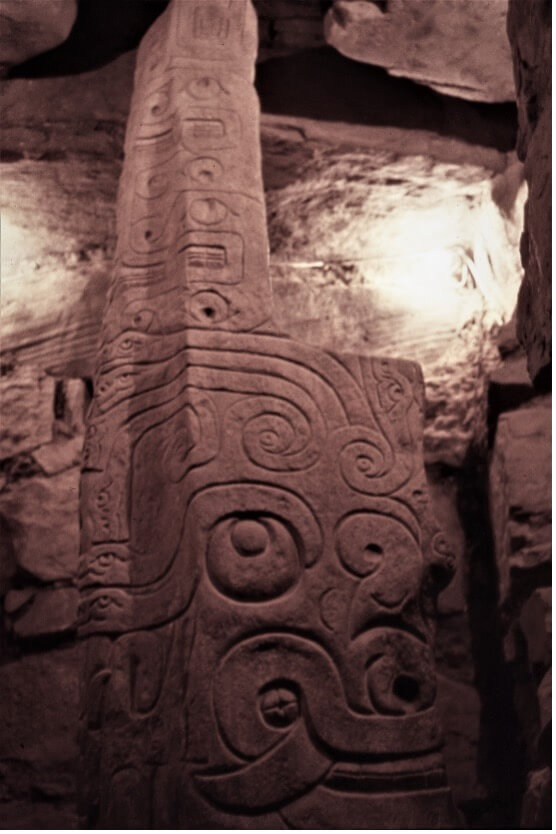

We entered the 2500-year-old temple located in the central highlands of Peru, the heart of the ancient Chavín civilisation. The passageway was dark, musty, and somewhat claustrophobic. At its end was a tiny chamber with a high vaulted ceiling. The light streaming in from a hole in the roof fell upon the statue, a vertical lance-shaped granite slab known as the Lanzon.

It was believed that the Lanzon had oracle powers and could speak as well as see into the past and future. I stood in this cramped room mesmerized, staring at this 4.5-metre object of worship, with the knowledge that generations of Chavín people have stood before me and performed their ritual and religious ceremonies. The moment was surreal, and I felt an overwhelming sense of spirituality that I have never experienced before.

I have been an exploration geologist for four decades, and one of the benefits of this occupation is exploring areas of a foreign country, particularly historical and archaeological sites. Peru is full of fascinating places, many associated with the ancient Inca civilization, such as Machu Picchu, the Sun and Moon Temples, the Royal Tomb of Sipan, the Nazca Lines, to name a few, and numerous ancient ruins spread along the entire coastal strip.

One of those opportunities arose when a good mate, Barry Henwood, and his wife Anna, visited Peru whilst I was there. The plan was to join up and spend a couple of days south of Lima in the Nazca area, then head north of Lima to visit the Cordillera Blanca, a mountain range, which is part of the Andes.

Read: Underrated travel destinations around the world

Nazca is located a long drive south of Lima, the road traversing a generally parched landscape with an occasional glimpse of the Pacific Ocean. Near Ica, one of the main population centres along the way, there are vast areas of vivid green cultivation, now a food basket for the area. The water table below has provided water for the previously arid landscape.

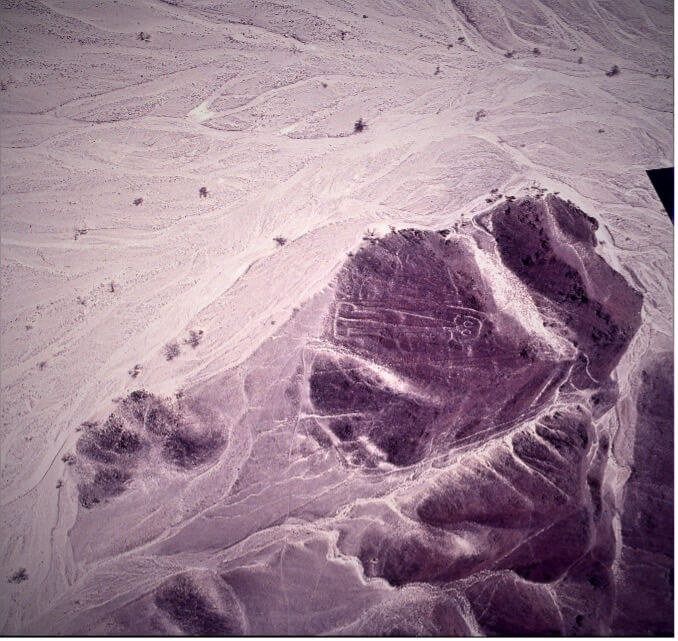

The Nazca Lines also occur in an arid area and are difficult to see from ground level. Hence, we took the opportunity to view the symbols from a local small aircraft, hired from the Nazca aeroclub. Barry was a long-term Qantas pilot, so I didn’t feel quite so nervous using a local plane with him in the co-pilot’s seat.

The flight was very worthwhile, as it highlighted the extent and unbelievably large size of many of the figures constructed on the desert floor. The Nazca lines are believed to have been formed over 1500 years ago. One of the most accepted theories is that they are related to a ritual practice for the worship of water.

Returning to Lima, we headed north on the main highway, then east into magnificent snow-capped peaks of the Cordillera Blanca. The road snaked its way upwards over 4000 metres in elevation, through a pass, and onto the town of Huaraz. The Cordillera Blanca extends for over 200km and has several peaks over 6000 metres high and 722 individual glaciers. The scenery is spectacular, with the seemingly crystal clear snow-capped peaks as a backdrop to the towns and valleys. Often in the valleys, the glacial melt forms beautiful, blue lakes known geologically as tarn lakes.

History records that in 1962, one of the highest peaks in the Cordillera Blanca named Mount Huascaran, located near Huaraz, was hit by a major earthquake.

Read: Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman take on South America

An enormous avalanche of ice, mud and rock thundered down the valley and wiped out numerous small villages and the main town of Yungay. The debris entered the Rio Santa and proceeded to create major damage for more than 150km downriver to the coast. It is estimated that more than 20,000 people died and is the deadliest glacier-related avalanche in history.

Whilst in the Huaraz area, we heard and read about the Chavín ruins and, as they were only a short detour off the Huaraz to Lima road, we decided to take a day trip. The Chavín culture is an extinct, pre-Columbian civilization and many artifacts were found in the ruins centred on the main historical population area known as Chavín de Huantar. The culture is thought to have been active in the northern Andean Highlands of Peru as far back as 3000 years ago and is believed to be the first religious cult in the Andes.

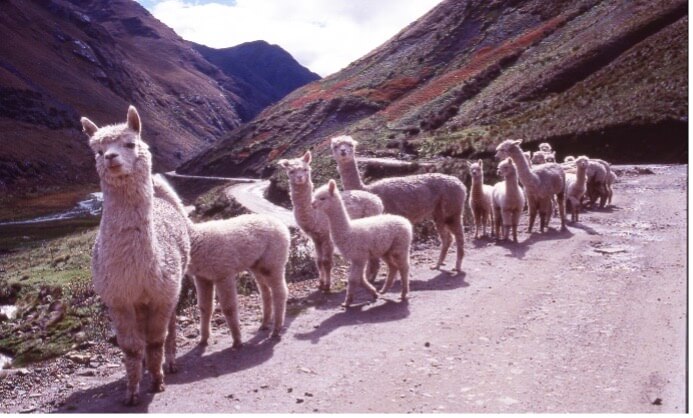

The unkempt gravel road leading into Chavín turned out to be very windy and slow, traversing numerous valleys and ridges. The scenery remained spectacularly photogenic, particularly the mountain peaks, local children and alpacas walking along the road edges.

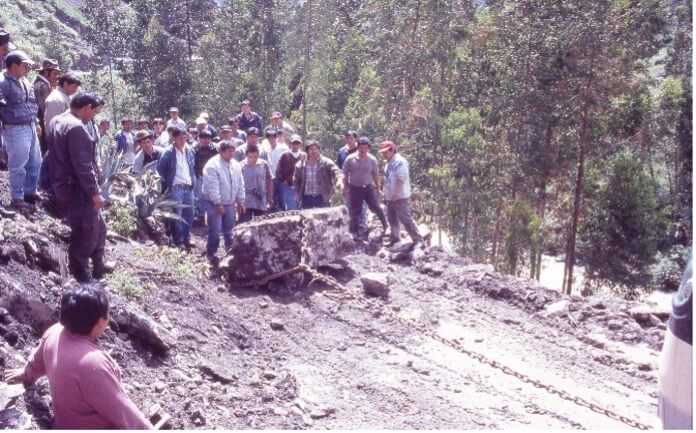

Just short of Chavín, on a very narrow steep-sided part of a single lane section of the road, we rounded a corner only to find it blocked by a bus with its occupants milling about. On inspection, we found that a huge boulder, which I reckon weighed several tonnes, had dislodged from the hillside above and blocked the road. Whilst we watched, and in typical country ingenuity, the people located a chain, wrapped it around the boulder and used the bus to drag it to the roadside.

The remaining short trip into Chavín was uneventful and the first impression of seeing the large sunken courtyard and temple remnants was somewhat unimpressive.

The ruins have deteriorated, unsurprisingly, due to their extreme antiquity and no doubt also due to tomb raiders and locals building houses over the long term out of pilfered stone. Standing in an old doorway framed by black basalt and white sandstone lintels, we immediately wondered if it had some significance relating to opposites such as black and white, night and day or the sun and the moon!

However, there was no doubt about its history upon observing some of the hieroglyphs and carvings still preserved on rock faces today.

Read: The best of South America

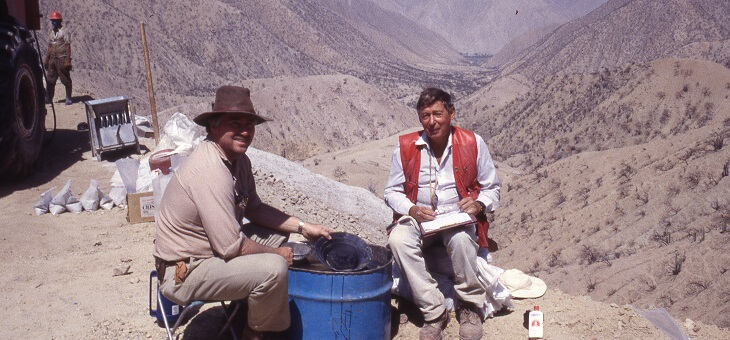

The best was yet to come as my company’s senior geologist in Peru, Robert Plenge, who was also with us on this trip, had a conversation with a local guard, who revealed the presence of numerous underground chambers.

One of these chambers contained Lanzon, the most noted discovery in the area, carved beautifully with feline shapes. Although the ruins were closed, Robert convinced the guard to allow us entry into the passageway and statue chamber (no doubt helped by a few coins passing hands!).

Time had passed quickly, and in front of us was a very long drive back to Lima that evening, but we all felt that we had experienced one of the most unforgettable days in our lives.

What did you think of David’s story? Is Peru on your travel wish list? Please let us know in the comments section below.

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.